Excerpts From Criticizing Photographs by Terry Barrett

About Art Criticism

This digest is about reading and doing photography criticism so that you can

better appreciate photographs by using critical processes. Unfortunately, we

usually don’t equate criticism with appreciation because in everyday language

the term criticism has negative connotations: It is used to refer to the act

of making judgments, usually negative judgments, and the act of expressing disapproval.

In mass media, critics are portrayed as judges of art: Reviewers in newspapers

rate restaurants with stars, and critics on television rate movies with thumbs

up or thumbs down or from I to 10, constantly reinforcing judgmental aspects

of criticism. Of all the words critics write, those most often quoted are judgments:

“The best play of the season!” “Dazzling!” “Brilliant”

These words are highlighted in hold type in movie and theater ads because these

words sell tickets. But they constitute only a few of the critic’s total

output of words, and they have been quoted out of context. These snippets have

minimal value in helping us reach an understanding of a play or a movie.

Critics are writers who like art and choose to spend their lives thinking and

writing about it. Bell hooks, a critic and scholar of African American cultural

studies, writes this about writing: “Seduced by the magic of words in childhood,

I am still transported, carried away, writing and reading. Writing longhand

the first drafts of all my works, I read aloud to myself, performing the words

to hear and feel them. I want to be certain I am grappling with language in

such a way that my words live and breathe, that they surface from a passionate

place inside me.”’ Peter Schjeldahl, a poet who now writes art criticism

as a career, writes that “I get front art a regular chance to experience

something-or perhaps everything, the whole world-as someone else, to replace

my eyes and mind with the eyes and mind of another for a charged moment.”’

Christopher Knight who has written art criticism for the Los Angeles Times since

1989, left a successful career as a museum curator to write criticism precisely

because he wanted to be closer to art: “The reason I got interested in

a career in art in the first place is to be around art and artists. I found

that in museums you spend most of your time around trustees and paperwork.”’

Some critics don’t want to be called critics because of the negative connotations

of the term. Art critic and poet Rene Ricard, writing in Artforum, says: “In

point of fact I’m not an art critic. I am an enthusiast. I like to drum

up interest in artists who have somehow inspired me to be able to say something

about their work. ,4 Michael Feingold, who writes theater criticism for the

Village Voice, says that “criticism should celebrate the good in art, not

revel in its anger at the bad.” 5 Similarly, Lucy Lippard is usually supportive

of the art she writes about, but she says she is sometimes accused of not being

critical, of not being a critic at all. She responds, “That’s okay

with me, since I never liked the term anyway Its negative connotations place

the writer in fundamental antagonism to the artists.”6 She and other critics

do not want to be thought of as being opposed to artists.

DEFINING CRITICISM

The term criticism is complex, with several different meanings. In the language

of aestheticians who philosophize about art and art criticism, and in the language

of art critics, criticism usually refers to a much broader range of activities

than just the act of judging. Morris Weitz, an aesthetician interested in art

criticism, sought to discover more about it by studying what critics do when

they criticize art .7 He took as his test case all the criticism ever written

about Shakespeare’s Hamlet, After reading the volumes of Hamlet criticism

written through the ages, Weitz concluded that when critics criticize they do

one or more of four things: They describe the work of art, they interpret it,

they evaluate it, and they theorize about it. Some critics engage primarily

in descriptive criticism; others describe, but primarily to further their interpretations;

still others describe, interpret, evaluate, and theorize. Weitz drew several

conclusions about criticism, most notably that any one of these four activities

constitutes criticism and that evaluation is not a necessary part of criticism.

He found that several critics criticized Hamlet without ever judging it.

When critics criticize, they do much more than express their likes and dislikes-and

much more than approve and disapprove of works of art. Critics do judge artworks,

and sometimes negatively, but their judgments more often are positive than negative:

As Rene Ricard says, “Why give publicity to something you hate?” When

Schjeldahl is confronted by a work he does not like, he asks himself several

questions: “‘Why would I have done that if I did it? is one of my

working questions about an artwork. (Not that I could. This is make-believe.)

My formula of fairness to work that displeases me is to ask, ‘What would

I like about this if I liked it? When I cannot deem myself an intended or even

a possible member of a work’s audience, I ask myself what such an audience

member must be like.”’ Michael Feingold thinks it unfortunate that

theater criticism in New York City often prevents theatergoing rather than encourages

it, and he adds that “as every critic knows, a favorable review with some

substance is much harder to write than a pan.”’ Abigail Solomon-Godeau,

who writes frequently about photography, says there are instances when it is

clear that something is nonsense and should be called nonsense, but she finds

it more beneficial to ask questions about meaning than about aesthetic worth.

“What do I do as a critic in a gallery?” Schjeldahl asks. He answers:

“I learn. I walk up to, around, touch if I dare, the objects, meanwhile

asking questions in my mind and casting about for answers-all until mind and

senses are in some rough agreement, or until fatigue sets in.” Edmund Feldman,

an art historian and art educator, has written much about art criticism and

defines it as “informed talk about art.”” He also minimizes the

act of evaluating, or judging, art, saying that it is the least important of

the critical procedures. A. D. Coleman, a pioneering and prolific critic of

recent photography, defines what he does as “the intersecting of photographic

images with words.”” He adds: “I merely look closely at and into

all sorts of photographic images and attempt to pinpoint in words what they

provoke me to feel and think and understand.” Morris Weitz defines criticism

as “a form of studied discourse about works of art. It is a use of language

designed to facilitate and enrich the understanding of art.” 13

Throughout this book the term criticism will not refer to the act of negative

judgment; it will refer to a much wider range of activities and will adhere

to this broad definition: Criticism is informed discourse about art to increase

understanding and appreciation of art. This definition includes criticism of

all artforms, including dance, music, poetry, painting, and photography “Discourse”

includes talking and writing. “Informed” is an important qualifier

that distinguishes criticism from mere talk and uninformed opinion about art.

Not all writing about art is criticism. Some art writing, for example, is journalism

rather than criticism: It is news reporting on artists and artworld events rather

than critical analysis.

A way of becoming informed about art is by critically thinking about it. Criticism

is a means toward the end of understanding and appreciating photographs. In

some cases, a carefully thought out response to a photograph may result in negative

appreciation or informed dislike. More often than not, however, especially when

considering the work of prominent photographers and that of artists using photographs,

careful critical attention to a photograph or group of photographs will result

in fuller understanding and positive appreciation. Criticism should result in

what Harry Broudy, a philosopher promoting aesthetic education, calls “enlightened

cherishing.”” Broudy’s “enlightened cherishing” is

a compound concept that combines thought (by the term enlightened) with feeling

(by the term cherishing). He reminds us that both thought and feeling are necessary

components that need to be combined to achieve understanding and appreciation.

Criticism is not a coldly intellectual endeavor.

KINDS OF CRITICISM

In an editorial in the journal of Aesthetic Education, Ralph Smith distinguishes

two types of art criticism, both of which are useful but serve different purposes:

exploratory aesthetic criticism and argumentative aesthetic criticism. In doing

exploratory aesthetic criticism, a critic delays judgments of value and attempts

rather to ascertain an object’s aesthetic aspects as completely as possible,

to ensure that readers will experience all that can be seen in a work of art.

This kind of criticism relies heavily on descriptive and interpretive thought.

Its aim is to sustain aesthetic experience. In doing argumentative aesthetic

criticism, after sufficient interpretive analysis has been done, critics estimate

the works positive aspects or lack of them and give a full account of their

judgments based on explicitly stated criteria and standards. The critics argue

in favor of their judgments and attempt to persuade others that the object is

best considered in the way they have interpreted and judged it, and they are

prepared to defend their conclusions.

Ingrid Sischy, editor and writer, has written criticism that exemplifies both

the exploratory and argumentative types. In a catalogue essay accompanying the

nude photographs made by Lee Friedlander,” Sischy pleasantly meanders in

and through the photographs and the photographer’s thoughts, carefully

exploring both and her reactions to them. We know, in the reading, that she

approves of Friedlander and his nudes and why, but more centrally, we experience

the photographs through the descriptive and interpretive thoughts of a careful

and committed observer. In an essay she wrote for the New Yorker about the popular

journalistic photographs made by Sebastiao Salgado, however, Sischy carefully

and logically and cumulatively builds an argument against their worth, despite

their great popularity in the art world.20 She clearly demonstrates argumentative

criticism that is centrally evaluative, replete with the reasons for and the

criteria upon which she based her negative appraisal.

Andy Grundberg, a former photography critic for the New York Times, perceives

two basic approaches to photography criticism: the applied and the theoretical.

Applied criticism is practical, immediate, and directed at the work; theoretical

criticism is more philosophical, attempts to define photography, and uses photographs

only as examples to clarify its arguments. Applied criticism tends toward journalism;

theoretical criticism tends toward aesthetics.”

Examples of applied criticism are reviews of shows, such as those written by

A. D. Coleman. Coleman also writes theoretical criticism as in his “Directorial

Mode” article. Other examples of theoretical criticism are the writings

of Allan Sekula, such as his essay “The Invention of Photographic Meaning,”

in which he explores how photographs mean and how photography signifies. He

is interested in all of photography, in photographs as kinds of pictures, and

refers to specific photographs and individual photographers only to support

his broadly theoretical arguments. Similarly Roland Barflies’s book, Camera

Lucida: Reflections on Photography, is a theoretical treatment of photography

that attempts to distinguish photography from other kinds of picture making.

In her writing about photography, Abigail Solomon-Godeau draws from cultural

theory, feminism, and the history of art and photography to examine ideologies

surrounding making, exhibiting, and writing about photographs. Her writing is

often criticism about criticism. Later in this book we will explore in detail

theories of art and photography, theoretical criticism, and how theory influences

both criticism and photography.

Grundberg also identifies another type of criticism as “connoisseurship,”

which he rejects as severely limited. The connoisseur, of wine or photographs,

asks “Is this good or bad?” and makes a proclamation based on his

or her particular taste. This kind of criticism, which is often used in casual

speech and sometimes found in professional writing, is extremely limited in

scope because the judgments it yields are usually proclaimed without supporting

reasons or the benefit of explicit criteria, and thus they are neither very

informative nor useful. Statements based on taste are simply too idiosyncratic

to be worth disputing. As Grundberg adds, “Criticism’s task is to

make arguments, not pronouncements.” This book is in agreement with Grundberg

on these points.

STANCES TOWARD CRITICISM

Critics take various stances on what criticism should be and how it should be

conducted. Abigail Solomon-Godeau views her chosen critical agenda as one of

asking questions~ “Primarily, all critical practices-literary or artistic-should

probably be about asking questions. That’s what I do in my teaching and

it’s what I attempt to do in my writing. Of course, there are certain instances

in which you can say with certainty, ‘this is what’s going on here,’

or ‘this is nonsense, mystification or falsification.’ But in the

most profound sense, this is still asking-what does it mean, how does it work,

can we think something differently about it 1121

Kay Larson, who is also concerned with explanation of artworks, says that she

starts writing criticism “by confronting the work at the most direct level

possible suspending language and removing barriers. It’s hard and it’s

scary-you keep wanting to rush back in with judgments and opinions, but you’ve

got to push yourself back and be with the work. Once you’ve had the encounter,

you can try to figure out how to explain it, and there are many ways to take

off-through sociology, history, theory, standard criticism, or description.””

Grace Glueck sees her role as a critic as being one of informing members of

the public about works of art: She aspires to “inform, elucidate, explain,

and enlighten.”” She wants “to help a reader place art in a context,

establish where it’s coming from, what feeds it, how it stacks up in relation

to other art.” Glueck is quick to add, however, that she needs to take

stands “against slipshod standards, sloppy work, imprecision, mistaken

notions, and for good work of whatever stripe.”

Coleman specified, in 1975, his premises and parameters for critical writing:

A critic should be independent of the artists and institutions about which he/she

writes. His/her writing should appear regularly in a magazine, newspaper, or

other forum of opinion. The work considered within that writing should be publicly

accessible and at least in part should represent the output of the critic’s

contemporaries and/or younger, less established artists in all their diversity

And he/she should be willing to adopt openly that skeptic’s posture which

is necessary to serious criticism.

These are clear statements of what Coleman believes criticism should be and

how it should be conducted. He is arguing for an independent, skeptical criticism

and for critics who are independent of artists and the museums and galleries

that sponsor those artists. He is acutely aware of possible conflicts of interest

between critic and artist or critic and institutional sponsor: He does not want

the critic to be anyone’s’s mouthpiece but rather to be an independent

voice. Coleman argues that because criticism is a public activity, the critic’s

writing should be available to interested readers, and that the artwork which

is criticized should also be open to public scrutiny. This would presumably

preclude a critic’s visiting an artist’s studio and writing about

that work, because that work is only privately available.

Coleman distinguishes between curators and historians who write about art, and

critics. He argues that curators, who gather work and show it in galleries and

museums, and historians, who place older work in context, write from privileged

positions: The historian’s is the privilege of hindsight; the curator’s

is the power of patronage. Coleman cautions that the writer, historian, curator,

or critic who befriends the artist by sponsoring his or her work will have a

difficult time being skeptical. He is quick to point out, however, that skepticism

is not enmity or hostility. Coleman’s goal is one of constructive, affirmative

criticism, and he adds: “The greatest abuses of a critic’s role stem

from the hunger for power and the need to be liked. ,21

Mark Stevens agrees that distinctions should be maintained between writing criticism

and writing history: “The trouble with acting like an art historian is

that it detracts from the job critics can do better than anybody else, and that

is to be lively, spontaneous, impressionistic, quick to the present-shapers,

in short, of the mind of the moment. 1130

Lucy Lippard is a widely published independent art critic who assumes a posture

different from Coleman’s, and her personal policies for criticism are in

disagreement with those of his just cited. She terms her art writing “advocacy

criticism.”” As an “advocate critic” Lippard is openly leftist

and feminist and rejects the notion that good criticism is objective criticism.

Instead, she wants a criticism that takes a political stand. She seeks out and

promotes “the unheard voices, the unseen images, or the unconsidered people.”

She chooses to write about art that is critical of mainstream society and which

is therefore not often exhibited. Lippard chooses to work in partnership with

socially oppositional artists to get their work seen and their voices heard.

Lippard also rejects as a false dichotomy the notion that there should be distance

between critics and artists. She says that her ideas about art have consistently

emerged from contact With artists and their studios rather than from galleries

and magazines. She acknowledges that the lines between advocacy, promotion,

and propaganda are thin, but she rejects critical objectivity and neutrality

as false myths and thinks her approach is more honest than that of critics who

claim to be removed from special interests.

Several readers and critics themselves have complained that criticism is too

often obscure, too difficult to read, and at times incomprehensible. Peter Schjeldald,

with some self-deprecating humor, writes that “I have written obscurely

when I could get away with it. It is very enjoyable, attended by a powerful

feeling of invulnerability.” Then, with less sarcasm, he adds: “Writing

clearly is immensely hard work that feels faintly insane, like painting the

brightest possible target on my chest. To write clearly is to give oneself away.

“42 This book tries to give ideas away by making them clear and thus accessible-especially

when they are difficult ideas —to anyone interested in knowing them.

THE VALUE OF CRITICISM

The value of reading good criticism is increased knowledge and appreciation

of art. Reading about art with which we are unfamiliar increases our knowledge.

If we already know and appreciate an artwork, reading someone else’s view

of it may expand our own if we agree, or it may intensify out own if we choose

to disagree and formulate counterarguments.

There are also considerable advantages for doing criticism. Marcia Siegel, dance

critic for the Hudson Review and author of several books of dance criticism,

talks about the value for her of the process of writing criticism: “Very

often it turns out that as I write about something, it gets better. Its not

that I’m so enthusiastic that I make it better, but that in writing, because

the words are an instrument of thinking, I can often get deeper into a choreographer’s

thoughts or processes and see more logic, more reason. “43

Similarly, A. D. Coleman began studying photography and writing photography

criticism in the late 1960’s because he realized that photography was shaping

him and his culture; he wanted to know more about it and “came to feel

that there might be some value to threshing out, in public and in print, some

understandings of the medium’s role in our lives. 44 For him the process

of criticizing was valuable in understanding photographs, and he hoped that

his thinking in public and in print would help him and others to better understand

photographs and their effects on viewers.

If the process of criticism is personally valuable even for frequently published,

professional critics, then it is likely that there are considerable advantages

for others who are less experienced with criticizing art. An immediate advantage

of thoughtful engagement with an artwork is that the observer’s viewing

time is slowed down and measurably prolonged. This point is obvious but important:

Most people visiting museums consider an artwork in less than five seconds.

Five seconds of viewing compared to hours and hours of crafting by the artist

seems woefully out of balance. Considering descriptive, interpretive, and evaluative

questions about an artwork ought to significantly expand one’s awareness

of an artwork and considerably alter one’s perception of the work.

In criticizing an art object for a reader or viewer, critics must struggle to

translate their complex jumble of thoughts and feelings about art into words

that can be understood first by themselves and then by others. Everyday viewers

of art can walk away from a picture or an exhibit with minimal responses, unarticulated

feelings, and incomplete thoughts. Critics who view artworks as professionals,

however, have a responsibility to struggle with meaning and address questions

that the artwork poses or to raise questions that the artwork does not.

Critics usually consider artworks from a broader perspective than the single

picture or the single show. They put the work in a much larger context of other

works by the artist, works by other artists of the day, and art of the past.

They are able to do this because they see much more art than does the average

viewer-they consider art for a living. Their audiences will not be satisfied

with one-word responses, quick dismissals, or empty praises. Critics have to

argue for their positions and base their arguments on the artwork and how they

understand it. Viewers who consider art in the way that a critic would consider

it will likely increase their own understanding and appreciation of art-that

is the goal and the reward.

Describing Photographs

DEFINING DESCRIPTION

To describe a photograph or an exhibition is to notice things about it and to

tell another out loud or in print, what one notices. Description is a data-gathering

process, a listing of facts. Descriptions are answers to the questions: “What

is here?

What am I looking at? What do I know with certainty about this image ?”

Theanswers are identifications of both the obvious and the not so obvious. Even

whencertain things seem obvious to critics, they point them out because they

know thatwhat is obvious to one viewer might be invisible to another. Descriptive

informationincludes statements about the photograph’s subject matter, medium,

anandthen more generally, about the photographer’s casual environmnet including

information about the photographer who made it, the times during which it was

made, and the social milieu from which it emerge Descriptive in inforrmation

is true (or false accurate (or inaccurate), factual (or contrary to fact): Either

Richard Avedon used an 8- by 10-inch Deardorff view camera or he didnt; either

he exposed more than 17,000 sheets of film or he didn’t. Descriptive statements

are verifiable by observation and an appeal to factual evidence. Although in

principle descriptive claims can be shown to be true or false, in practice critics

sometimes find it difficult to do so.

Critics obtain descriptive information from two sources-internal and external.

They derive much descriptive information by closely attending to what can be

seen within the photograph. They also seek descriptive information from external

sources including libraries, the artists who made the pictures, and press releases.

Describing is a logical place to start when viewing an exhibition or a particular

photograph because it is a means of gathering basic information on which understanding

is built. Psychologically, however, we often want to judge first, and our first

statements often express approval or disapproval. There is nothing inherently

wrong with judging first as long as judgments are informed and relevant information

is descriptively accurate. Whether we judge first and then revise a judgment

based on description, or describe and interpret first and then judge, is a matter

of choice. The starting point is not crucial, but accurate description is an

essential part of holding defensible critical positions. Interpretations and

judgments that omit facts or are contrary to fact are seriously flawed.

Critics inevitably and frequently describe, but in print they don’t necessarily

first describe, next interpret, and then judge. They might first describe to

themselves privately before they write, but in print they might start with a

judgment, or an interpretive thesis, or a question, or a quotation, or any number

of literary devices, in order to get and hold the attention of their readers.

They would probably be dreadfully boring if they first described and then interpreted

and then judged. In the same sentence critics often mix descriptive information

with an interpretive claim or with a judgment of value. For our immediate aim

of learning the descriptive process of criticism, however, we are sorting and

highlighting descriptive data in the writing of critics.

DESCRIBING SUBJECT MATTER

Descriptive statements about subject matter identify and typify persons, objects,

places, or events in a photograph. When describing subject matter, critics name

what they see and also characterize it.

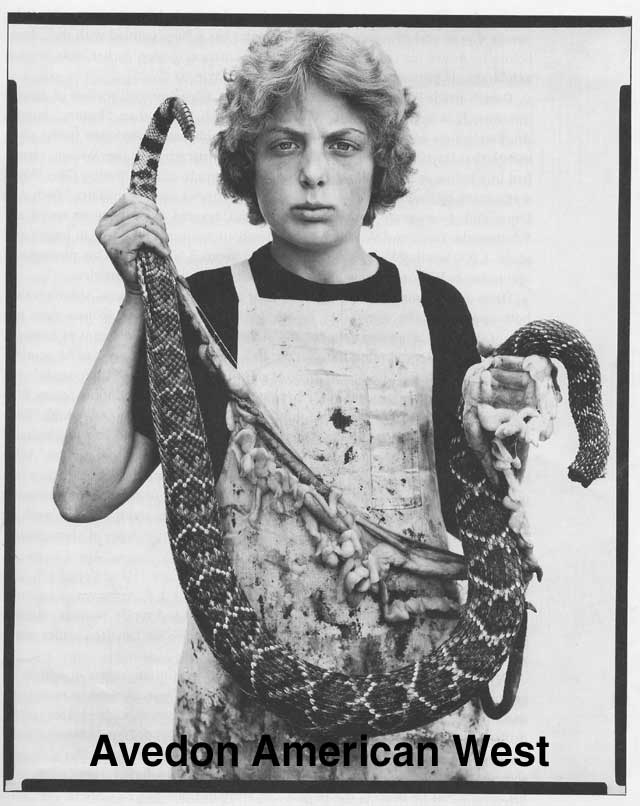

Avedon’s subject matter is mostly people and is relatively uncomplicated-usually

one person to a photograph. But as we have just seen, describing that subject

matter is not an easy task. The subject matter of many other photographs is

also simple, but when criticizing it, we characterize what is there. Edward

Weston’s subject matter for an entire series of photographs is green peppers.

The subject matter of a Minor White photograph is bird droppings on a boulder.

Irving Penn’s subject matter for a series of photographs is cigarette butts.

Some photographers utilize a lot of simple objects as their subject matter.

In a series of still lifes, Jan Groover “took her camera to the kitchen

sink” and photographed complicated arrangements of kitchen utensils such

as knives, forks, spoons, plates, cups, plastic glasses and glass glasses, pastry

and aspic molds, metal funnels, whisks, plants, and vegetables.” Most of

the objects are recognizable, but some are abstracted in the composition so

that they are “surfaces and textures” and not recognizable on the

basis of what is shown. Although in real life Groover’s subject matter

is a pie pan, on the basis of what is seen in the photograph it can be identified

only as “a brushed aluminum surface” or “a glistening metallic

plane.” The subject matter of many abstract works can be described only

with abstract terms, but critics still can and should describe it.

The subject matter of some photographs is seemingly simple but actually very

elusive. Cindy Sherman’s work provides several examples. Most of these

photographs are self-portraits, so in one sense her subject matter is herself.

But she titles black and white self-portraits made between 1977 and 1980 “Untitled

Film Stills.” In them she pictures herself, but as a woman in a wide variety

of guises from hitchhiker to housewife. Moreover, these pictures look like stills

from old movies.She also made a series of “centerfolds” for which

she posed clothed and in the manner of soft-porn magazine photographs. So what

is the subject matter of these pictures? In a New York Times review, Michael

Brenson names the subject matter of the film still photographs “stock characters

in old melodramas and suspense films.” But Eleanor Hearin writing in Afterimage,

says that both the -self-portraits and the film still I photographs directly

refer to “the cultural construction of femininity.” 13

They are pictures of Cindy Sherman and pictures of Cindy Sherman disguised asothers;

they are also pictures of women as women are represented in cultural artifacts

such as movies, magazines, and paintings, especially as pictured by male producers,

directors, editors, painters, and photographers. To simply identify them as

“portraits” or “portraits of women” or “self-portraits”

or “self-portraits of Cindy Sherman” would be inaccurate and in a

sense would be to misidentify them.

DESCRIBING FORM

Form refers to how the subject matter is presented. Ben Shahn, the painter and

photographer who made photographs for the Farm Security Administration in the

1930s, said that form is the shape of content. Descriptive statements about

a photograph’s form concern how it is composed, arranged, and constructed

visually We can attend to a photograph’s form by considering how it uses

what are called “for mal elements.” From the older artforms of painting

and drawing, photography has inherited these formal elements: dot, line, shape,

light and value, color, texture, mass, space, and volume. Other formal elements

identified for photographs include black and white tonal range; subject contrast;

film contrast; negative contrast; paper contrast; film formal; point of view,

which includes the distance from which the photograph was made and the lens

that was used; angle and lens; frame and edge; depth of field, sharpness of

grain; and degree of focus. Critics refer to the -ways photographers use these

formal elements as “principles ‘of design,” which include scale,

proportion, unity within variety, repetition and rhythm, balance, directional

forces, emphasis, and subordination.

Edward Weston identified some of the choices of formal elements the photographer

has when exposing a piece of film: “By varying the position of his camera,

his camera angle, or the focal length of his lens, the photographer can achieve

an infinite number of varied compositions with a single stationary subject.”

18 John Szarkowski reiterated what Weston observed over fifty years ago and

added an important insight: “The simplicity of photography lies in the

fact that it is very easy to make a picture. The staggering complexity of it

lies in the fact that a thousand other pictures of the same subject would have

been equally easy.” 19

In an essay for an exhibition catalogue of Jan Groover’s work, Susan Kismaric

provides a paragraph that is a wonderful example of how a critic can describe

form and its effects on subject matter:

The formal element put to most startling use in these pictures is the scale

of the objects in them. Houseplants, knives, forks, and spoons appear larger

than life. Our common understanding of the meaning of these pedestrian objects

is transformed to a perception of them as exotic and mysterious. Arrangements

of plates, knives, and houseplants engage and delight our sight through their

glamorous new incarnation while they simultaneously undermine our sense of their

purpose in the natural world. Meticulously controlled artificial light contributes

to this effect. Reflections of color and shapes on glass, metal, and water,

perceived only for an instant or not at all in real life, are stilled here,

creating a new subject for our contemplation. The natural colors of the things

photographed are intensified and heightened. Organic objects are juxtaposed

with manmade ones. Soft textures balance against, and touch, hard ones. The

sensuous is pitted against the elemental 20

The formal elements to which Kismaric refers are light, color, and texture;

the principles of design are scale arrangements of objects, and juxtapositions.

She cites scale as the most dominant design principle and then describes the

effects of Groover’s use of scale on the photographs and our perception

of them. She identifies the light as artificial and tells us that it is meticulously

controlled. The colors are natural; some of the shapes are manufactured and

others are organic, and they are juxtaposed. She identifies the textures as

soft and hard, sensuous and elemental. Kismaric’s description of these

elements, and her explanation of their effects, contributes to our knowledge

and enhances our appreciation of Groover’s work.

Kismaric’s paragraph shows how a critic simultaneously describes subject

matter and form and also how in a single paragraph a critic describes, interprets,

and evaluates. To name the objects is to be descriptive, but to say how the

objects become exotic and mysterious is to interpret the photographs. The tone

of the whole paragraph is very positive. After reading the paragraph we know

that Kismaric thinks Groover’s photographs are very good and we are provided

reasons for this judgment based on her descriptions of the photographs.

DESCRIBING MEDIUM

The term medium refers to what an art object is made of. In a review of Bea

Nettles’s photographs in the 1970s, A. D. Coleman described the media Nettles

was using: “stitching, sensitized plastics and fabrics, dry and liquid

extraphotographic materials ... hair, dried fish, Keel Aid, feathers, and assorted

other things.”” The medium of Sandy Skoglund’s Walking on Eggshells,

1997, can simply and accurately be said to be Cibachrome, or color photograph,

but in the installation she constructed for the photograph, Skoglund uses the

media of whole, empty eggshells (some filled with plaster), cast paper bathroom

fixtures (sink, bathtub, toilet, mirror), cast paper wall tiles with relief-printed

images, cold-cast (bonded-bronze) sculptures of snakes and rabbits, over a variable

floor space of thirty square feet. To make Spirituality of the Flesh, she bought

eighty pounds of raw hamburger with which to cover the walls in the final photograph,

and she used orange marmalade and strawberry preserves to color the walls and

floor of The Wedding. Descriptive statements about a picture’s medium usually

identify it as a photograph, an oil painting, or an etching. They may also include

information about the kind and size of film that was used, the size of the print,

whether it is black and white or in color, characteristics of the camera that

was used, and other technical information about how the picture was made, including

how the photographer photographs.

Thus the description of medium involves more than just using museum labels,

as in labeling. Jan Groover’s images as “three chromogenic color prints,”

or “platinumpalladium print,” or “Gelatin-silver print.”

To fully describe the medium a photographer is using is not only to iterate

facts about the process he or she uses, the type of camera, and kind of print,

but also to discuss these things in light of the effects their use has on their

expression and overall impact. Critics might more fully explore these effects

as part of their interpretation or judgment of the work, but they ought to explicitly

mention the properties of the medium in the descriptive phase of criticism.

DESCRIBING STYLE

Style indicates a resemblance among diverse art objects from an artist, movement,

time period, or geographic location and is recognized by a characteristic handling

of subject matter and formal elements. Neo-expressionism is a commonly recognized,

recent style of painting, and pictorialism, “directorial” photography,

28 and the “snapshot aesthetic” 29 are styles of photography. To consider

a photographers style is to attend to what subjects he or she chooses to photograph,

how the medium of photography is used, and how the picture is formally arranged.

Attending to style can be much more interpretive than descriptive. Labeling

photographs “contemporary American” or “turn of the century”

is less controversial than is labeling them “realistic” or “straight”

or “manipulated” or “documentary,” The critics of Avedon’s

work being considered here are particularly interested in determining whether

his style is “documentary” or “fictional,” or “fashion.”

Determining Avedon’s style involves considerably more than describing,

but it does include descriptions of whom he photographs, how he photographs

them, and what his pictures look like.

COMPARING AND CONTRASTING

A common method of critically analyzing a photographers work is to compare and

contrast it to other work by the same photographer, to other photographers’

works, or to works by other artists. To compare and contrast is to see what

the work in question has in common with and how the work differs from another

body of work.

Critics need not limit their comparisons of a photographer to another photographer.

Wilson makes comparative references between Avedon and several others of various

professions, most of whom are not photographers but rather literary sources

he knows and figures in fashion and popular culture: Sam Shepard, Edward Curtis,

Mathew Brady, August Sander, Joan Didion, Norman Mailer, Truman Capote, Evil

Knievel, Salvador Dali, Elsa Schiaparelli, Charles James, Andy Warhol, Tom Wolfe,

Calvin Klein, Georgia O’Keeffe, Ansel Adams, and Irving Penn. Wilson compares

Avedon to other storytellers and to others who bridged the gap between fashion

and art, because he interpretively understands Avedon to be telling stories

and attempting to transcend fashion with his photographs.

Of all the critics considered here, Weiley makes the most use of in-depth comparisons,

paying particular attention to the similarities and mostly the differences between

Avedon’s work and that of Robert Frank, August Sander, and Diane Arbus.

She cites Robert Frank’s book, The Americans (1959), because like Avedon’s

it is “a harsh vision of America”” and because both men are outsiders

to the cultures they photographed: Frank is Swiss, and Avedon is not a cowboy.

To compare Avedon with Frank, Sander, and Arbus, Weiley has to describe each

ones photographs and manner of working and then specify how each photographer’s

work is different from and similar to that of the others.

INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL SOURCES OF INFORMATION

We have seen that a critic can find much to mention about the photograph by

attending to subject, form, medium, and style. And, as mentioned earlier, critics

often go to external sources to gather descriptive information that increases

understanding of that photograph. In their writings the critics of Avedon’s

work each used much information not decipherable in the photographs. By looking

only at his American West photographs, a viewer cannot tell that Avedon’s

exhibited photographs were selected from 17,000 negatives, that he held 752

shooting sessions, that the work was commissioned by the Amon Carter Museum,

or that they were made by a famous fashion photographer who had a large body

of images made previously. This information comes from a variety of sources,

including press releases, interviews with the artist, the exhibition catalogue,

and knowledge of photography history. To compare and contrast Avedon’s

work with his own earlier work and with the work of others, including nonvisual

work, each of the critics went to external sources.

The test of including or excluding external descriptive information is one of

relevancy The critic’s task in deciding what to describe and what to ignore

is one of sorting the relevant information from the irrelevant, the insightful

from the trivial and distracting. When engaging in criticism, however, one would

not want to substitute biography for criticism or to lose sight of the work

amid interesting facts about the artist.

DESCRIPTION AND INTERPRETATION

It is probably as impossible to describe without interpreting as it is to interpret

without describing. A critic can begin to mentally list descriptive elements

in a photograph, but at the same time he or she has to constantly see those

elements in terms of the whole photograph if those elements are to make any

sense. But the whole makes sense only in terms of its parts. The relationship

between describing and interpreting is circular, moving from whole to part and

from part to whole.

Though a critic might want to mentally list as many descriptive elements as

possible, in writing criticism he or she has to limit all that can be said about

a photograph to what is relevant to providing an understanding and appreciation

of the picture. Critics determine relevancy by their interpretation of what

the photograph expresses. In a finished piece of criticism, it would be tedious

to read descriptive item after descriptive item, or fact after fact, without

having some understanding on which to hang the facts. That understanding is

based on how the critic interprets and evaluates the picture, or how one evaluates

it. At the same time, however, it would be a mistake to interpret without having

considered fully what there is in the picture, and interpretations that do not

(or worse, cannot) account for all the descriptive elements in a work are flawed

interpretations. Similarly, it would be irresponsible to judge without the benefit

of a thorough accounting of what we are judging.

DESCRIPTION AND EVALUATION

Joel-Peter Witkin is a controversial photographer who makes controversial photographs.

Critics judge him differently; and their judgmerns, positive or negative or

ambivalent, influence their descriptions of his work. Cynthia Chris clearly

disapproves of the work: “Witkin’s altered photographs are representations

of some of the most repressed and oppressed images of human behavior and appearance,””

whereas Hal Fischer writes that “Joel-Peter Witkin, maker of bizarre, sometimes

extraordinary imagery, is one of the most provocative artists to have emerged

in the past decade.” 36 And Gene Thornton of the New York Times calls Witkin

“one of the great originals of contemporary photography,”37 Their

evaluations, positive or negative, are often mixed into their descriptions.

For example, Gary Indiana uses the phrases “smeared with burntin blotches”

and “the usual fuzz around the edges” to describe some formal characteristics

of Witkin’s prints,” and Bill Berkson describes the same edges as

“syrupy.” 39 These are not value-neutral descriptors but rather descriptors

that suggest disapproval. Another critic, Jim Jordan, talks about “Witkin’s

incredible range of form definition within the prints” and claims that

Witkin’s surface treatments “inform the viewer that these are works

of art. ‘140 Jordan’s phrase “incredible range of form definition”

is also a mix of description and judgment, with positive connotations.

In published criticism, descriptions are rarely value-free. Critics color their

descriptions according to whether they are positive or negative about the work,

and they use descriptors that are simultaneously descriptive and evaluative

to influence the reader’s view of the artwork. Critics attempt to be persuasive

in their writing. Readers, however, ought to be able to sort the critic’s

descriptions from judgments, and value-neutral descriptions from value-laden

descriptions, however subtly they are written, so that they can more intelligently

assent or dissent.

Novice critics can find it beneficial to attempt to describe a photograph without

connoting positive or negative value judgments about it. They may then be more

sensitive to and aware of when descriptions are accurate and neutral and when

they are positively or negatively judgmental.

THE IMPORTANCE OF DESCRIPTION TO READERS

As we have seen throughout the chapter, description is an extremely important

activity for critics, established or novice, because it is a time for “getting

to know” a piece of art, especially if that art is previously unknown and

by an unfamiliar artist. Descriptions are also important to readers, because

they contain crucial and interesting information that leads them to understand

and appreciate images. Descriptions provide information about photographs and

exhibitions that readers may never get to see and otherwise would not experience

at all. Descriptions are also the basis on which they can agree or disagree

with the critic’s interpretation and judgment.

Describing photographs and reading descriptions of photographs are particularly

important activities because people tend to look through photographs as if they

were windows rather than pictures. Because of the stylistic realism of many

photographs, and because people know that photographs are made with a machine,

people tend to consider photographs as if they were real events or living people

rather than pictures of events or people. Pictures are not nature and they are

not natural; they are human constructs. Photographs, no matter how objective

or scientific, are the constructions of individuals with beliefs and biases,

and we need to consider them as such. To describe subject, form, medium, and

style is to consider photographs as pictures made by individuals and not to

mistake them for anything more or less.

Description is not a prelude to criticism; description is criticism. Careful

descriptive accounts by insightful critics using carefully constructed language

offers the kind of informed discourse about photographs that increases our understanding

and appreciation of photographs.

Interpreting Photographs

AS A CULTURE we are perhaps more accustomed to thinking of interpreting poems

and paintings than photographs. But all photographs-even simple ones-demand

interpretation in order to be fully understood and appreciated. They need to

be recognized as pictures about something and for some communicative and expressive

purpose. Joel-Peter Witkin’s bizarre photographs attract interpretive questions

and thoughts because they are different from our common experiences, but many

photographs look natural and are sometimes no more cause of notice than tables

and trees. We accept photographs in newspapers and on newscasts as facts about

the world and as facts that, once seen, require no scrutiny.

Photographs made in a straightforward, stylistically realistic manner are in

special need of interpretation. They look so natural that they seem to have

been made by themselves, as if there had been no photographer. If we consider

how these photographs were made, we may accept them as if they were made by

an objective, impartial, recording machine. Andy Grundberg, reviewing an exhibition

of National Geographic photographs, makes this point about these kinds of photographs:

“As a result of their naturalism and apparent effortlessness, they have

the capacity to lull us into believing that they are evidence of an impartial,

uninflected sort. Nothing could be further from the truth.”’

Nothing could be further from the truth because photographs are partial and

are inflected. People’s knowledge, beliefs, values, and attitudes-heavily

influenced by their culture-are reflected in the photographs they take. Each

photograph embodies a particular way of seeing and showing the world. Photographers

make choices not only about what to photograph but also about how to capture

an image on film, and often these choices are very sophisticated. We need to

interpret photographs in order to make it clear just what these inflections

are.

When looking at photographs, we tend -to -think of them as “innocent”-that

is, as bare facts, as direct surrogates of reality, as substitutes for real

things, as direct reflections. But there is no such thing as an innocent eye.

2 We cannot see the world and at the same time ignore our prior experience in

and knowledge of the world.

Philosopher Nelson Goodman puts it like this: as Ernst Gombrich insists, there

is no innocent eye. The eye comes always ancient to its work, obsessed by its

past and by old and new insinuations of the ear, nose, tongue, fingers, heart,

and brain. it functions not as an instrument self-powered and alone, but as

a dutiful member of a complex and capricious organism. Not only how but what

it sees is regulated by need and prejudice.3

If there is no such thing as the innocent eye, there certainly isn’t an

innocent camera. What Goodman says of the eye is true of the camera, the photograph,

and the “photographer’s eye” as well:

It selects, rejects, organizes, discriminates, associates, classifies, analyzes,

constructs. It does not so much mirror as take and make; and what it takes and

makes it sees not bare, as items without attributes, but as things, as food,

as people, as enemies, as stars, as weapons.

Thus, all photographs, even very straightforward, direct, and realistic-looking

ones, need to be interpreted. They are not innocent, free of insinuations and

devoid of prejudices, nor are they simple mirror images. They are made, taken,

and constructed by skillful artists and deserve to be read, explained, analyzed,

and deconstructed.

DEFINING INTERPRETATION

While describing, a critic names and characterizes all that he or she can see

in the photograph. Interpretation occurs whenever attention and discussion move

beyond offering information to matters of meaning. Hans-Georg Gadamer, the European

philosopher known for his extensive work on the topic of interpretation, says

that to interpret is “to give voice to signs that don’t speak on their

own.” To interpret is to account for all the described aspects of a photograph

and to posit meaningful relationships between the aspects.

When one is acting as a critic, to interpret a photograph is to tell someone

else, in speech or in writing, what one understands about a photograph, especially

what one thinks a photograph is about. Interpreting is telling about the point,

the meaning, the sense, the tone, or the mood of the photograph. When critics

interpret a work of art, they seek to find out and tell others what they think

is most important in an image, how its parts fit together, and how its form

affects its subject. Critics base interpretations on what is shown in the work

and on relevant information outside of the work, or what in Chapter 2 we called

the photograph’s causal environment. Interpretations go beyond description

to build meaning. Interpretations are articulations of what the interpreter

understands an image to be about. Interpreters do more than uncover or discover

meaning; they offer new language about an image to generate new meaning.

Another way of understanding interpretation is to think of all photographs as

metaphors in need of being deciphered. A metaphor is an implied comparison between

unlike things. Qualities of one thing are implicitly transferred to another.

Verbal metaphors have two levels of meaning: the literal and the implied. Visual

metaphors also have levels of meaning: what is shown and what is implied. A

photograph always shows us something as something. In the simple sense, a portrait

of a man shows us the man as a picture-that is, as a flat piece of paper with

clusters of tones from a lightsensitive emulsion. In another simple sense, a

photograph always shows us a certain aspect of something. A portrait of Igor

Stravinsky by Arnold Newman shows us Stravinsky somehow, as something. In Goodman’s

words, “the object before me is a man, a swarm of atoms, a complex of cells,

a fiddler, a friend, a fool, and much more.” The photograph represents

the thing or person as something or as some kind of person. Newman’s portrait

of Stravinsky shows the man sitting at a piano. In a more complex way, however,

the portrait of Stravinsky shows him not only as a man sitting at a piano but

also as a brilliant man, or a profound man, or a troubled man. The more complex

“as” requires interpretation. To miss the metaphoric and to see only

the literal is to misunderstand the expressive aspects of photographs.

INTERPRETIVE CLAIMS AND ARGUMENTS

The main interpretive questions that critics ask of photographs are “What

do these photographs mean? What are they about?” All interpretations share

a fundamental principle-that photographs have meanings deeper than what appears

on their surfaces. The surface meaning is obvious and evident about what is

pictured, and the deeper meanings are implied by what is pictured and how it

is pictured. If one looks at the surface of Cindy Sherman’s self-portrait

photographs, for example, which were discussed in Chapter 2, they seem to be

about a woman on the road hitchhiking or a housewife in a kitchen. Less obviously

however, they are pictures of the artist -herself, in various guises, and they

are self-portraits. Because of how the subject photographed the film stills

can also be understood to refer to-media representations and to how popular

women And, in an interpretive statement by Eleanor Heartney, they are, less

obviously still, about “the cultural construction of femininity Heartney

and other critics who consider Sherman’s work are not content to understand

the film stills simply as pictures of women doing various things, self-portraits

of Cindy Sherman, or self-portraits of an artist in artful disguises. They look

beyond the surface for deeper meanings about femininity, the representation

of femininity, and culture.

INTERPRETIVE PERSPECTIVES

Critics interpret photographs from a wide range of perspectives. Following are

brief interpretations by several photography scholars, each written from a different

vantage point to show the variety of strategies critics use to decipher images.

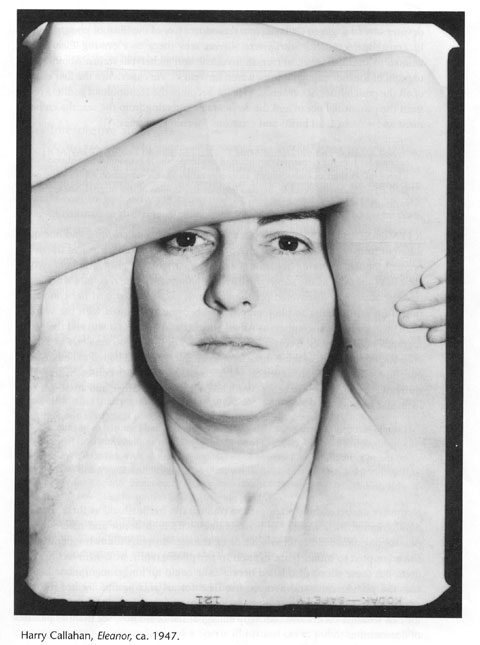

The first three interpretations are by different writers on the same images,

Harry Callahan’s photographs of his wife, Eleanor, which are titled Eleanor,

Port Huron, 1954. These examples show how critics can vary in their interpretations

and how their various interpretations of the same images can alter our perceptions

and understandings. Then interpretations of other photographers’ works

are used as examples of a variety of interpretive strategies.

Three Interpretations of Eleanor

A COMPARATIVE INTERPRETATION John Szarkowski claims

that most people who have produced lasting images in the history of photography

have dealt with aspects of their everyday lives and that Callahan is one of

them. For many decades he has photographed his wife, his child, his neighborhoods,

and the landscapes to which he escapes. Szarkowski notes that Callahan is different

from most photographers who work from their personal experiences. Whereas they

try to make universal statements from their specifics, Callahan, according to

Szarkowski, “draws us ever more insistently inward toward the center of

this] private sensibility... Photography has been his method of focusing the

meaning of that life.... Photography has been a way of living.”

AN ARCHETYPAL INTERPRETATION In American Photography,

Jonathan Green devotes several pages to Callahan and reproduces five of the

Eleanor photographs.15 In contradistinction to Szarkowski, Green sees them as

elevating Eleanor the woman to an impersonal, universal, mythical, and archetypal

status. About a photograph of Eleanor nor emerging from water, he writes: “We

experience the fons et origo of all the possibilities of existence. Eleanor

becomes the Heliopolitan goddess rising from the primordial ocean and the Terra

Mater emerging from the sea: the embodiment and vehicle of all births and creations.”

Green continues:

Over and over again, Callahan sees Eleanor in the context of creation: she has

become for him the elemental condition of existence, she is essential womanhood,

a force rather than an embodiment, an energy rather than a substance, As such

she appears cold and inaccessible, beyond the human passions of lust or grief.

She is the word made flesh.

A FEMINIST INTERPRETATION In a personally revealing

critique, and one quite different from the two preceding interpretations, Diane

Neumaier traces the development of her thinking regarding women, particularly

photographers’ wives, including Eleanor, as the subject matter of photographs.

She recounts when as an undergraduate she discovered photography and excitedly

changed her concentration from printmaking to photography She became acquainted

with the work of such prominent photographers as Alfred Stieglitz and Emmet

Gowin and their photographs of their wives, Georgia O’Keeffe and Edith

Gowin. Neumaier was thrilled with the romanticism of these three famous couples,

and she hoped to be like them and do similar work. However, as years passed,

and as her consciousness grew through the experiences of being simultaneously

a wife, mother, and artist, her conflicts also increased:

I simultaneously wanted to be Harry Alfred, or Emmet, and I wanted to be their

adored captive subjects. I wanted to be Eleanor, or Edith and have my man focus

on me and our child, and I wanted to be Georgia, passive beauty and active artist.

Together these couples embodied all my most romantic, contradictory, and impossible

dreams.’,’

Neumaier unsuccessfully attempted to photograph her husband as these men had

photographed their wives: “To possess one’s wife is to honor and revere

her. To possess one’s husband is impossible or castrating.” In years

following her divorce, she attempted to immortalize her son in her photographs,

as Gowin has his children. But these efforts also failed because she could no

longer manipulate her son into the photographs and because her time for art

was limited by her role as a mother. She had to reevaluate those early pictures

of the photographers’ wives and, for her, feminist conclusions strongly

emerged; she could now see them as pictures of domination:

These awe-inspiring, beautiful photographs of women are extremely oppressive.

They fit the old traditions of woman as possession and woman as giver and sacrificer.

In this aesthetically veiled form of misogyny, the artist expects his wife to

take off her clothing, then he photographs her naked (politely known as nude),

and after showing everybody the resulting pictures he gets famous.... The subtle

practice of capturing, exposing, and exhibiting one’s wife is praised as

sensitive.

Other Interpretive Strategies

PSYCHOANALYTIC INTERPRETATION Laurie

Simmons has made a series of photographs using dolls and figurines in different

dollhouse settings. In writing about Simmons’s work, Anne Hoy states that

these female dolls are trapped in environments in which they are dwarfed by

TV sets and out-of-scale grocery items. In contrast to the trapped dolls, Simmons

later suggested freedom by photographing cowboy dolls outside, but their liberation

was illusory because even the grass in the pictures outsized them. in the early

1980s, Simmons made a series of swimmers using figurines and live nude models

underwater. About these, Hoy writes: “In a Freudian interpretation, they

suggest the equivalence of drowning and sexual surrender and the sensations

of weightlessness associated with those twin abandonments. ,17

FORMALIST INTERPRETATION Some

interpreters base their interpretations of images solely or primarily on considerations

of the image’s formal properties. Richard Misrach has been photographing

the desert for a number of years, first at night with flash in black and white

and then in the day in color. Kathleen McCarthy Gauss offers this interpretation

of one of the color photographs, The Santa Fe, 1982: “a unique configuration

of space, light, and events.” She continues:

A highly formalized balance is established between the nubby ground and smooth,

blue sky, both neatly cordoned off along the horizon by red and white boxcars.

The most reductive, minimal composition is captured. The train rolls along just

perceptibly below the horizon, bisecting the frame into two horizontal registers.

Yet, this is another illusion, for the train is in fact standing Still.18

Gauss’s treatment of this image mixes her descriptive observations with

interpretive insights. She is content to leave this image with these observations

and insights about its compositional arrangement and not to conjecture further.

SEMIOTIC INTERPRETATION Roland Barthes’s

interpretation of the Panzani advertisement detailed earlier is an example of

an interpretation that seeks more to understand how an image means than what

it means. Bill Nichols uses a similar interpretive strategy to understand a

Sports Illustrated cover published during the first week of football season

when Dan Devine began coaching the Notre Dame football team. The photographic

cover shows a close-up of the quarterback ready to receive a hike and an inset

of Devine gesturing from the sideline. Nichols points out that the eyeline of

the two suggests that they are looking at each other and that their expressions

suggest that the quarterback is wondering what to do and the coach is providing

him an answer. Nichols interprets the contrast between the large size of the

photograph of the quarterback and the smaller photograph of the coach as signifying

the brawn of the player and the brain of the coach. He surmises:

This unspoken bond invokes much of the lure football holds for the armchair

quarterback-the formulation of strategy, the crossing of the boundary between

brain/brawn-and its very invocation upon the magazine’s cover carries with

it a promise of revelation: within the issue’s interior, mysteries of strategy

and relationship will be unveiled. 19

MARXIST INTERPRETATION Linda Andre provides a

sample of the kinds of questions a Marxist critic might ask about an exhibition

of Avedon’s celebrity photographs: We might look at the enormous popularity

of Richard Avedon’s photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art as attributable

as much to the public’s hunger for pictures of the rich, famous and stylish-a

hunger usually sated not by museums but by the daily tabloids-as to his photographic

virtuosity To broaden the focus even more, we might ask what kind of society

creates such a need-obviously one where enormous class inequalities exist and

where there is little hope of entering a different class-and what role Avedon’s

pictures might play in the maintenance of this system. 20

Andre explains that one of her attempts as a critic is to place photographs

in the context of social reality-to interpret them as manifestations of larger

societal developments and social history, as well as photography and art history.

INTERPRETATION BASED ON STYLISTIC INFLUENCES Critics

often explain or offer explanatory information about a photographer’s work

by putting it into a historical and stylistic context. In an introduction to

the work of Duane Nichols, for example, Anne Hoy writes that Michols’s

images “pay homage to the spare, realistic styles and dreamlike subjects

of the Surrealist painters René Magritte, Giorgio de Chirico, and Balthus.

,21 Such contextual information helps us to see the work of one photographer

in a broader framework, and it implicitly reinforces the notion that all art

comes in part from other art or that all artists are influenced by other artists’

work. Such comparisons demand that readers have certain knowledge: If they do

not know the work of Magritte, de Chirico, and Balthus, for example, then Hoy’s

interpretive claim will not have much explanatory force for them. If they do

possess such knowledge, however, then they can examine Michals’s work in

this broader context.

BIOGRAPHICAL INTERPRETATION Critics also provide

answers to the question “Why does the photographer make these kinds of

images (rather than some other kind)?” One way of answering this question

is to provide biographical information about the photographer. In his introduction

to the work of Joel-Peter Witkin discussed in Chapter 2, Van Deren Coke provided

a lot of biographical information about the photographer .22 In writing about

the images, Coke strongly implies a cause-and-effect relationship between Witkin’s

life experiences and the way his images look. For instance, after relating that

Witkin’s family had little extra money, Coke says: “This explains

in part why we find in Witkin’s photographs echoes of a sense of deprivation

and insecurity.” For some critics, however, such a jump from an artist’s

biography to a direct account of his or her images is too broad a leap. Regarding

Coke’s claim, for instance, we could first ask to be shown that there is

a sense of deprivation and insecurity in the work, and then we could still be

skeptical that the reason, even “in part,” is because Witkin’s

family had little extra money There could be another reason or many reasons

or different reasons or no available reasons why there is, if indeed there is,

a sense of deprivation and insecurity in Witkin’s photographs.

INTENTIONALIST INTERPRETATION It is a natural

inclination to want to know what the maker intended in an image or a body of

work. So when critics interview artists, they seek their intended meanings for

their work, how they understand their own photographs. Well-known photographers

are frequently invited to travel and talk about their work in public, and sometimes

they explain their intentions in making their photographs. Although the views

of the makers about their own work can and should influence our understanding

of their work, those views should not determine the meaning of the work or be

used as the standard against which other interpretations are measured. We will

discuss the problems of intentionalism as an interpretive method later in this

chapter.

INTERPRETATION BASED ON TECHNIQUE Critics also

provide answers to the question “How does the photographer make these images?”

In answering this question, the critic may provide much interesting information

about how the photographer workshis or her choice of subject, use of medium,

printing methods, and so forth. Although these accounts provide useful information,

they are descriptive accounts about media and how photographers manipulate media

rather than interpretive accounts of what the photographs mean or what they

express by means of the surface and beyond the surface. Interpretations usually

account for how the photographs are made and then consider the effects of the

making on the meanings.

Combinations of Interpretive Approaches

When critics interpret photographs, they are likely to use a hybrid of approaches

rather than just one approach. For his analyses of photographs, Bill Nichols,

for example, claims to draw on Marxism, psychoanalysis, communication theory,

semiotics, structuralism, and the psychology of perception. A feminist may or

may not use a Marxist approach, and Marxist approaches are many, not just one.

A critic may also choose among approaches depending on the kinds of photographs

being considered. Finally, a critic may consider one photograph from several

of these perspectives at a time, resulting in several competing interpretations.

This approach raises issues about the correctness of interpretations.

“RIGHT” INTERPRETATIONS

“Surely there are many literary works of art of which it can be said that

they are understood better by some readers than by others. ,23 Monroe Beardsley

is an aesthetician who made this comment about interpreting literature. And

because some people understand artworks better than others do, concludes Beardsley,

some interpretations are better than others. If someone understands a photograph

better than I do, then it would be desirable for me to know that interpretation

to increase my own understanding. If someone has a better interpretation than

I do, then it follows that better (and worse) interpretations are possible.

In essence, not all interpretations are equal; some are better than others,

and some can be shown to be wrong. Unlike Beardsley, however, the aesthetician

Joseph Margolis takes a softer position on the truth and falsity of interpretations-the

position that interpretations are not so much true or false as they are plausible

(or implausible), reasonable (or unreasonable) .24 This more flexible view of

interpretation allows us to accept several competing interpretations as long

as they are plausible. Instead of looking for the true interpretation, we should

be willing to consider a variety of plausible interpretations from a range of

perspectives: modernist, Marxist, feminist, formalist, and so forth.

Although we will not use the term true for a good interpretation, we will use

such terms as plausible, interesting, enlightening, insightful, meaningful,

revealing, original; or conversely, unreasonable, unlikely, impossible, inappropriate,

absurd, farfetched, or strained. Good interpretations are convincing and weak

ones are not.

When people talk about art in a democratic society such as our own, they tend

to unthinkingly hold that everyone’s opinion is as good as everyone else’s.

Thus, in a discussion in which we are trying to interpret or evaluate an artwork

and a point of view is offered that is contrary to our own, we might say, “That’s

just your opinion,” implying that all opinions are equal and especially

that our own is equal to any other. Opinions that are not backed with reasons,

however, are not particularly

useful or meaningful. Those that are arrived at after careful thought and that

can be backed with evidence should carry weight. To dismiss a carefully thought

out opinion with a comment like “That’s just your opinion!” is

intellectually irresponsible. This is not to say that any reasoned opinion or

conclusion must be accepted, but rather that a reasoned opinion or conclusion

deserves a reasoned response.

Another widespread and false assumption in our culture about discussing art

goes something like this: “It doesn’t matter what you say about art,

because it’s all subjective anyway” This is extreme relativism about

art that doesn’t allow for truth and falsity, or plausibility and reasonability,

and that makes it futile to argue about art and about competing understandings

of art. Talk about art can be verifiable, if the viewer relates his or her statements

to the artwork. Although each of us comes to artworks with our own knowledge,

beliefs, values, and attitudes, we can talk and be understood in a way that

helps make sense of photographs; in this sense, our interpretations can be grounded

and defensible.

There are two criteria by which we can appraise interpretations: correspondence

and coherence .25 An interpretation ought to correspond to and account for all

that appears in the picture and the relevant facts pertaining to the picture.

If any items in the picture are not accounted for by the interpretation, then

the interpretation is flawed. Similarly, if the interpretation is too removed

from what is shown, then it is also flawed. The criterion of correspondence

helps to keep interpretations focused on the object and from being too subjective.

This criterion also “insists on the difference between explaining a work

of art and changing it into a different one.” 26 we want to deal with what

is there and not make our own work of art by seeing things not there or by changing

the work into something that we wish it were or which it might have been.

We also want to build an interpretation, or accept the interpretation, that

shows the photograph to be the best work of art it can be. This means that given

several interpretations, we will not choose the ones that render the photograph

insignificant or trivial but rather the ones that give the most credit to the

photograph-the ones that show it to be the most significant work it can be.

The criterion of correspondence also allays the fear of “reading too much

into” a work of art or photograph. If the interpretation is grounded in

the object, if it corresponds to the object, then it is probably not too far

removed from and is not reading too much into the photograph.

According to the second criterion, coherence, the interpretation ought to make

sense in and of itself, apart from the photograph. That is, it should not be

internally inconsistent or contradictory. Interpretations are arguments, hypotheses

backed by evidence, cases built for a certain understanding of a photograph.

The interpreter draws the evidence from what is within the photograph and from

his or her experience of the world. Either the interpretive argument is convincing

because it accounts for all the facts of the picture in a reasonable way, or

it is not convincing.

INTERPRETATIONS AND THE ARTIST’S INTENT

Minor White, the photographer and influential teacher of photography, once said

that “photographers frequently photograph better than they know.””

He was cautioning against placing too much emphasis on what photographers think

they have photographed. White placed the responsibility of interpretation on

the viewer rather than on the photographer, in response to the problem in criticism

of “intentionalism,” or what aestheticians refer to as “the intentional

fallacy”” Intentionalism is a faulty critical method by which images

(or literature) are interpreted and judged according to what the maker intended

by them. According to those who subscribe to intentionalism, if the photographer,

for instance, intended to communicate x, then that is what the image is about,

and interpretations are measured against the intent of the photographer. in

judging photographs, the critic attempts to determine what the photographer

intended to communicate with the photograph and then on that basis judges whether

the photographer has been successful or not. if the photographer has achieved

his or her intent, then the image is good; if not, the image is unsuccessful.

There are several problems with intentionalism as a critical method. First it

is difficult to find out what the intent of the photographer was. Some photographers

are unavailable for comment about their images; others don’t express their